“Every Cripple Has His Own Way of Walking” was published in December 1966, the same year that Ann Quin’s second novel, Three, appeared. Many of the tropes and techniques developed in her novels are here. Marginal characters with marginal lives roam, fruit is waxen, milk topped by a coagulated skin, shirt cuffs are tide-marked and one is kept awake by phlegmy coughs in the night. In Quin’s books, human perspective is generally found kneeling at keyholes, or pressing an ear against a flimsy partition wall. But through the eyes of the child through whom this narrative is focused, the world is more bewilderingly distant and irreal than ever. It is rendered in chopped syntax and anacolutha; meaning doesn’t so much accumulate as is falteringly established and then partially scrubbed out or welded on or overlaid. The verb “to be” is frequently redacted and therefore sentences describe whilst never quite bestowing existence upon. Objects lack solidity and consistency, events a sense of having actually occurred. The undifferentiated dialogue always conveys more or less than what is actually said. Stock phrases trail off because, well, they hardly need completing. Or, what’s actually meant has been redacted, and lies hidden somewhere behind the ellipses. Rather, what animates Quin’s work here and elsewhere is a profound dissatisfaction with abiding, with going through the motions, with, as she puts it, the “never changing rituals” of everyday life, together with the hope that something else might be possible . . .

On the occasion of the launch event for Issue 6 of Music & Literature Magazine at The Forum in Norwich, the British poet and Hungarian translator George Szirtes was invited to read a poem as a preface to Roman Yusipey's performance, on accordion, of the Ukrainian Victoria Polevà's Null, a composition written for Yusipey himself. Subsequent to that evening, Szirtes was moved to write a further poem inspired by and dedicated to Yusipey. Music & Literature is proud to publish both poems in their entirety . . .

A feature by Joanna Walsh

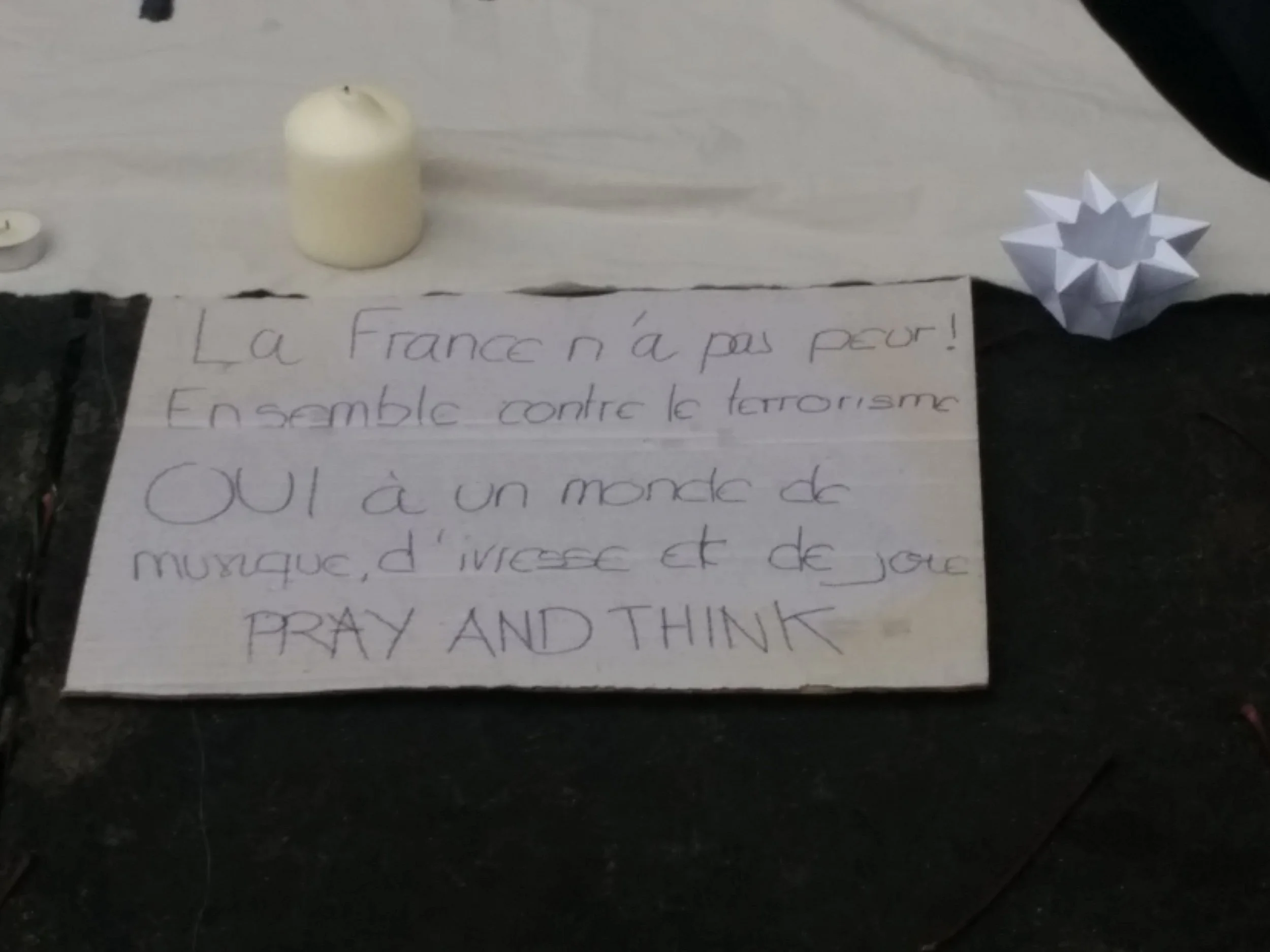

Last Sunday in Oxford I attended a vigil. Two to three hundred people, most of them French, walked from Radcliffe Square through the center of Oxford to the French Cultural Institute, La Maison Française. I stumbled my way through “La Marseillaise” (I can’t remember half the words), there was a minute’s silence, then people came forward to place, on a cloth, flowers, candles, newspaper clippings, scribbled notes, photographs, small, and sometimes unidentifiable objects. . .

A feature by Emily Cooke

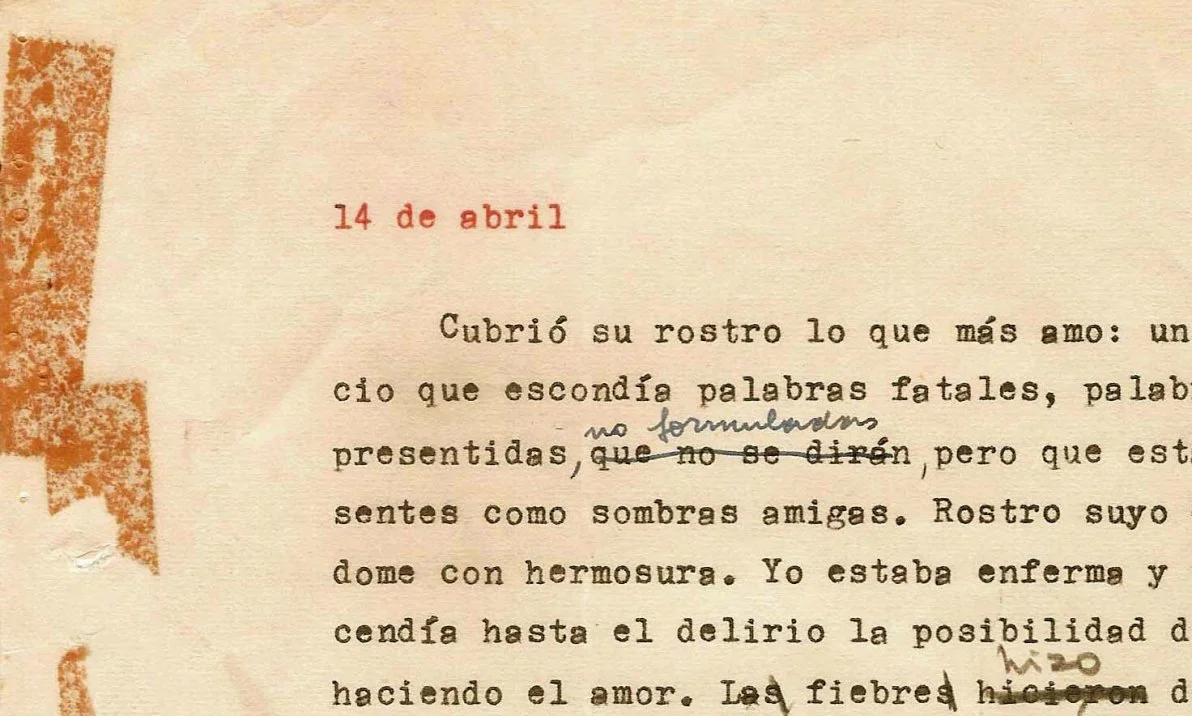

Alejandra Pizarnik's obsession with the form of her life—how it went, how it should go—is especially visible in her letters to her psychoanalyst, León Ostrov, a selection of which appears below. Pizarnik began seeing Ostrov in 1954, when she was eighteen. The analysis, which lasted barely more than a year, initiated a friendship that remained analytically alive long after it stopped being formally therapeutic. The conversation was not confined to Pizarnik’s “problems and melancholies,” as Ostrov would understatedly refer to the often debilitating mental illness of his former patient. Pizarnik and Ostrov shared their minor doings, riffed on books, discussed Pizarnik’s writing and career. Pizarnik visited Ostrov’s house and grew close with his family. Ostrov’s daughter, Andrea, remembers Pizarnik arriving at an elegant dinner party in a “furiously” red sweatshirt and pants. In 1960, when Pizarnik moved to Paris, she and Ostrov began regularly corresponding, and stayed in touch throughout the four years she lived abroad. The nineteen letters that survive this period (there are twenty-one in total; two date from earlier) showcase the young poet’s wit and spirit even as they reveal her anxieties. Pizarnik complains about her parents, insults her boss, mocks the Parisian literary elite (she’s appalled by Simone de Beauvoir’s screeching voice), wonders whether a poet should live artistically or like a “clerk,” and fantasizes about her artistic future. “I’m numbering the letters for our future biographers,” reads one postscript . . .

A feature by Daniel Medin

DM: To what extent did the war change your approach to writing? On the one hand the answer seems obvious: Berlin and Amsterdam became settings for your fiction, and the experience of exile a principal theme. And yet I was struck while rereading Lend Me Your Character, since the stories featured in that volume are remarkably consistent, despite having been published originally between 1981 and 2005.

DU: The war did not change my approach toward literature. I have always cared more about how things are written than what is being written about. But the war changed me. It brought with it new themes, preoccupations, and thoughts. And of course: exile, a changed life, a deeper knowledge of human nature, fresh stimulations. These were powerful experiences. However, I had no desire to convert them into a memoir or autobiography.

I would never judge the quality of a literary text by inspecting whether the writer’s experience was real or false; the text itself betrays the author. A careful reader only feels comfortable in the text when the author feels comfortable in there too: it’s a secret communication between them.