Review by Scott Esposito

Rafael Chirbes's On the Edge proved to be a chaotic, misanthropic opus from a literary heavyweight. Published earlier this year in a polished English translation by veteran Margaret Jull Costa, it is a book that demands attention. It is a major statement about contemporary Spain, one that is almost unbearably cynical and bitter, at times less a literary novel so much as a catalog of indignities, regrets, wrongdoing, decay, and general human awfulness. It is a book that offers the reader no hope, a book that may very well suggest that hope itself is an emotion that is simply naive in a Spain that has been crushed by malaiseand taken captive by oligarchs . . .

Review by Tim Rutherford-Johnson

Krauze’s unistic style of music closely followed Strzemiński’s manner of painting: flat on its surface, although potentially deeply layered. Where Strzemiński avoided a hierarchy of foreground and background, so Krauze avoids incident or drama in his music. Just as every part of a Strzemiński canvas is equal to every other, so every element of a Krauze work can be heard, in theory, in its first few seconds; and every subsequent moment continues to present all of those elements. Throughout the work’s duration essentially nothing new happens. However, that does not necessarily make it dull . . .

Review by Xenia Hanusiak

The responsibility for guiding audiences in the act of listening to classical music has historically rested on the shoulders of composers. In the United States, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thompson, and John Cage each brought a prolific pen to the discussion. In Europe, Pierre Boulez and more recently Heiner Goebbels have both asked us to reconsider the relationship between music and the audience. The baton of inquiry is now passing to contemporary visual artists. Two recent shows in New York have questioned the assumptions on which the act of listening seems to be founded. . .

Review by Lauren Goldenberg

Idra Novey's Ways to Disappear is a beckoning mix of comedy and noir, romance and violence. Perhaps above all else, it is a love letter to the art of translation. That most particular, intimate act is threaded throughout, and the question arises again and again: how do you know a person? Through words, or through blood? And aren’t relationships between people translations themselves, in a sense?

Review by Matthew Lorenzon

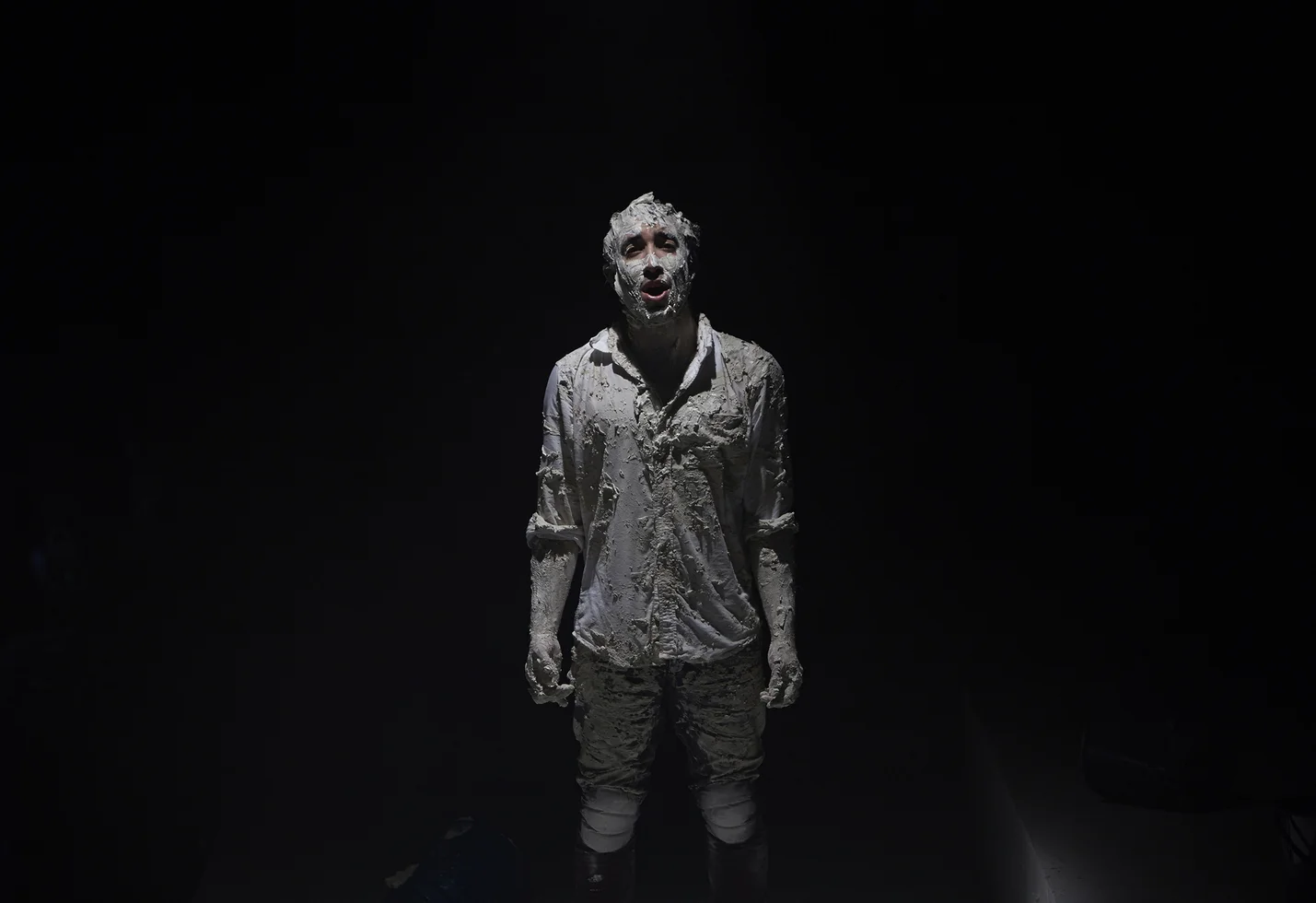

. . . Taking his cue from the novel’s binary of earth and air, each chord is mirrored by another, inversionally-symmetrical chord (that is, one that has been “flipped” vertically). Read from right to left, the grid’s pitch profile moves from the highest registers of the ensemble to the lowest, just as the characters move from halcyon Australia to the earthy mud of the battlefield. My immediate impression when hearing that Gyger had used a “landscape-like grid of pitches” was a slight internal groan. Representing the (generally flat) Australian landscape is a cliché of Australian composition. Seeing the grid, however, I understood that Gyger’s landscape is less a panorama than a bird’s-eye view of the world as Jim sees when he is taken up in a light aircraft. The grid may also resemble a battlefield with the inversionally-symmetrical chords forming opposing networks of mine holes and trenches

Review by Daniel Hartley

The stories in Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond feature a consistent narratorial voice: a female first-person narrator who recounts past events, hypothetical situations, and self-discoveries to an implied interlocutor. A young Englishwoman living in rural Ireland (or so we infer), the narrator is unreliable to the extent that she is often unsure as to what took place in the past, what her motivation was, or why she is even recounting this in the present. She is generally as much as of a mystery to herself as to the reader; indeed, the narrative motor of these stories is less plot than the narrator’s attempt to fathom why she did or did not do something, or what exactly the truth might be behind a particular trait she has remarked about herself . . .

Review by Will Rees

“We should be punished for thinking we can control everything, even death,” writes Portuguese journalist Susana Moreira Marques in her slim new volume Now and at the Hour of Our Death. Indeed, often we are. How can we prepare ourselves “for death and dying” while avoiding this fantasy of control which may simply serve to increase the height from which we fall? Moreira Marques’s book—translated into sharp, spare English by Julia Sanches—provides more than a few clues. Systematically rejecting every rhetorical and psychological trick we typically use to make light of death or gain a foothold in it, Moreira Marques nonetheless avoids stumbling blindly into pessimism. By turning a journalist’s unblinking eye to the concrete realities of dying, she allows something fragile, utterly realistic and quietly affirming to come to the fore . . .

Review by Daniela Cascella

This is a tale of transmission, disappearance, and utterance, of writing as it hovers at the edge of language, trafficking with the ephemeral and the unreliable; challenging the primacy of the written text through a compelling reflection on flow and interference, rhythms and non-origin. A tale of listening as the rebeginning of writing; of people missing but resounding through words whose meaning is lost (or maybe it was never there completely): it has to be made anew every time. A story of speech emerged from and given back to birds, wind and water, a story of speech into landscape. A tale of writing as divining and impure continuity.

Review by Liam Cagney

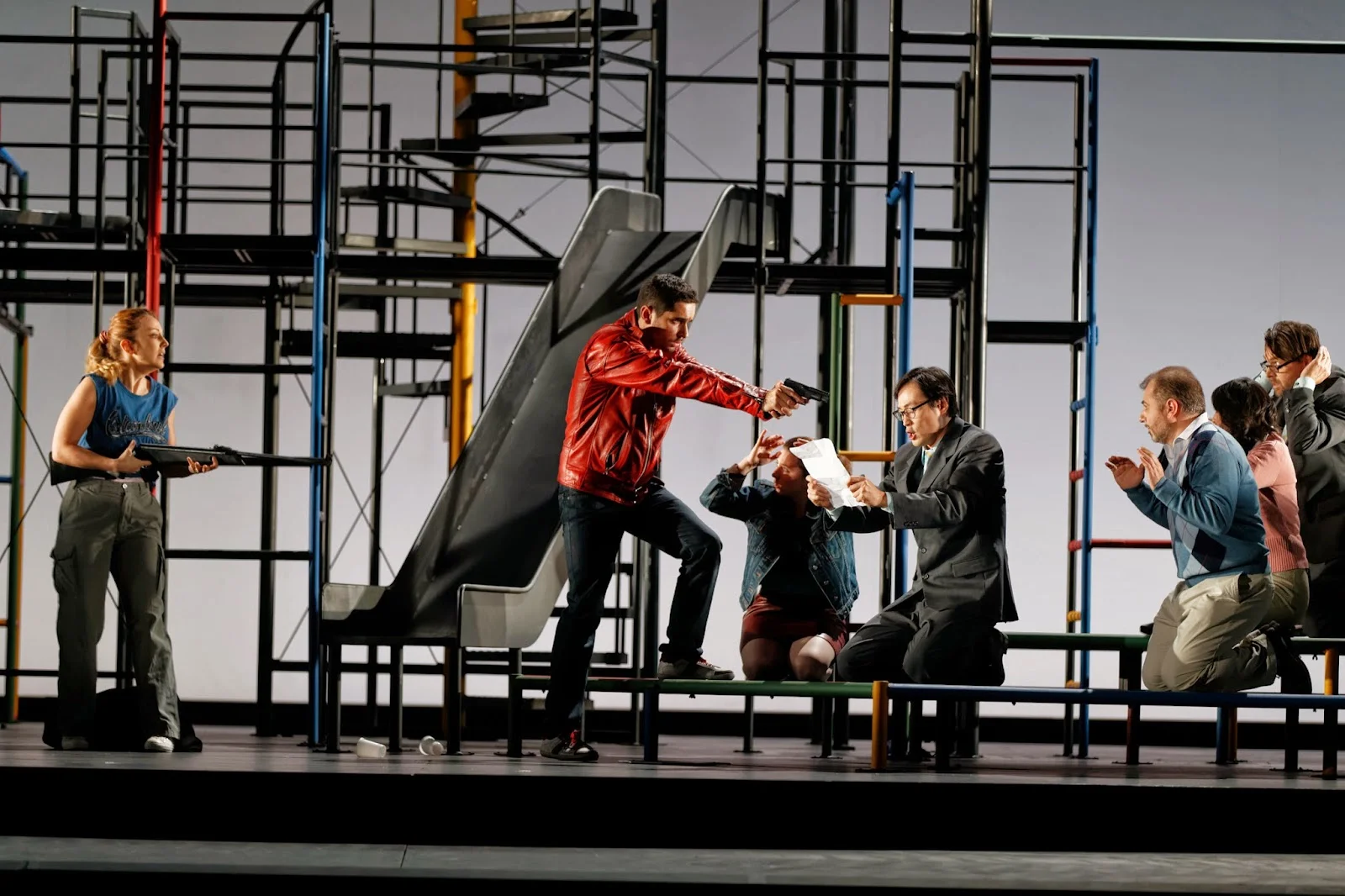

Tanguy Viel’s libretto for Les Pigeons d’argile transposes the tale to France in the past five or six years, with Hearst restyled as the French Patricia Baer (soprano Vannina Santoni). A love story takes central place: the relationship between terrorists Charlie (baritone Aimery Lefèvre) and Toni becomes threatened when Toni falls for the kidnapped Patty. Minor characters feature: Patty’s father Bernard Baer (bass-baritone Vincent Le Texier), a business magnate; Toni’s father Pietro (tenor Gilles Ragon), an aged socialist and caretaker of the Baer estate; and a police chief (mezzo Sylvie Brunet-Grupposo). That the Patty Hearst episode is transposed to France—site of the Revolutionary Republic, the Terror, the Paris Commune, the lost revolution of May ’68, and (now) the recent Islamic State terror attacks—is deliberately provocative. . .

Review by Nell Pach

No one’s ever really gone on the Internet. “With all this technology, absence has become a lie,” writes Hisham Bustani in The Perception of Meaning. Absent presence—that paradox of electronic communication—slowly emerges as a central motif in this enigmatic and yet wonderfully immersive novel...

Review by Jeremy M. Davies

When Dodge Rose first landed at my desk at Dalkey Archive Press, I thought it was a hoax. A trap. I showed it to my assistant editor of the time and he agreed: novels like Dodge Rose don’t come into one’s life in brown paper, humble, untrumpeted. It wasn’t possible, we said, that a young, Australian Beckett with virtually no publications to his name had just dropped in our laps. No, there was some sinister plot in the works. A plot to—well, what? Was this some éminence grise of the mainstream cutting loose and producing the high-modernist novel he or she had been lusting to write since their teenage infatuation with Ulysses? Or could this be one of Dalkey’s own authors—or employees?—submitting a novel under a false name to see if we would be able to sniff out the imposture? It even occurred to me to worry that Dodge Rose was, Ern Malley-wise, a prank, an attempt to snare a small press known for publishing “subversive” fiction into signing on a book written expressly to parody said fiction. There had to be a catch, no?

Review by Joshua Daniel Edwin

Although i mean i dislike that fate that i was made to where is Sophie Seita’s English translation of Uljana Wolf’s German poetry, this simple binary does justice to neither side of what it describes. Both texts, the original and the translation, are inter-lingual. They rely on linguistic multiplicity: they work in it; they are made of it . . .

Review by Bruno George

Berit Ellingsen's Not Dark Yet is ultimately a Robinsonade, its Crusoe, Brandon, willingly isolated in a cabin in the woods. Even the novel’s first line expresses harkens back to Crusoe the world-traveler: “Sometimes, in Brandon Minamoto’s dreams, he found a globe or a map of the world with a continent he hadn’t seen before.” But unlike Crusoe, Brandon doesn’t save himself and his isolate world through deep-sea salvaging and strict accounting. Standing before his cabin for the very first time, Brandon has a yielding, melting, anonymous experience that sharply separates him from Defoe’s energetic and autonomous Crusoe: “He closed his eyes and there was no body, and no world either, only the simple, singular nothingness he recognized as himself” . . .

Review by Anna Zalokostas

“How long does a thought take to form?” asks a woman in Vertigo, a collection of linked stories by British writer and illustrator Joanna Walsh. “Years sometimes. But how long to think it? And once thought it’s impossible to go back. How long does it take to cross an hour?” Sometimes it takes hours to finish a sentence, a lifetime to find a city from which it becomes possible to begin. Time in Vertigo doesn’t so much slow down as it does short-circuit; the present moment is suspended, each instant expanded. Stories pass by like slow motion film; long stretches of thought are torqued by the white noise of the ordinary. This is a liminal space that eludes situation, an amplified present that expands the possibilities of genre . . .

Review by Jordan Anderson

In Marcus's assessment, “Last Kind Word Blues” represents of the degree to which America inadvertently tends to cut its own mythology from the cloth of a deeply oppressed underclass that shares little resemblance to the “respectable” status quo. Akin to the lost-by-history legend of blues musician Robert Johnson, who left behind as little historical trace as possible, Wiley and Thomas were obscure blues artists who created songs for Paramount Records, a label notorious, Marcus notes, for the poor quality of their recordings (the label was begun as a sideline by a furniture company to sell records for the gramophones they hawked to customers). It is in the near-total obscurity of Wiley and Thomas that Marcus finds a sort of counterpoint to America as it would like to see itself . . .

Review by Rosie Clarke

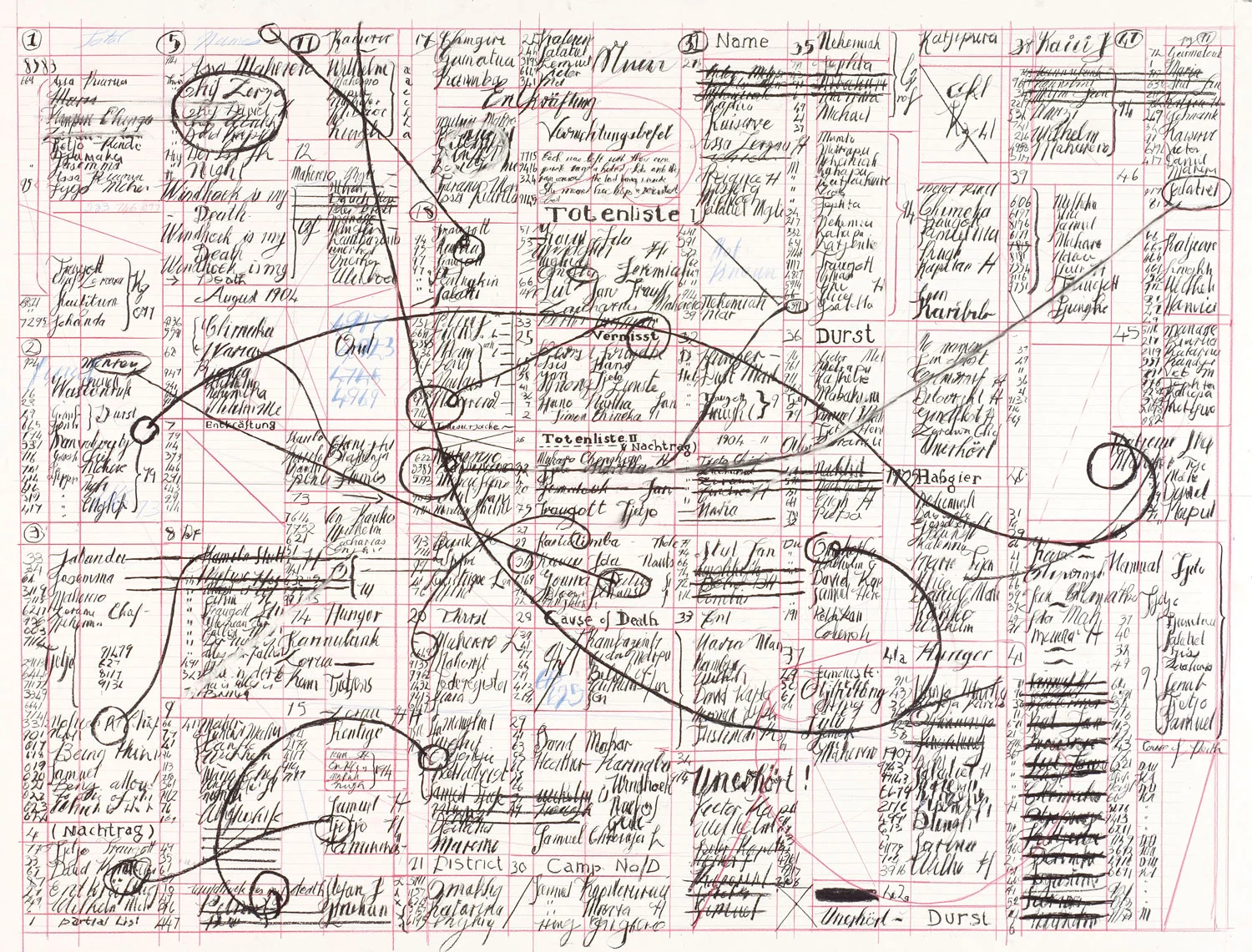

Critchley begins his Memory Theater with an arresting statement: “The fear of death slept for most of the day and then crept up late at night and grabbed me by the throat.” His relationship with mortality thus cemented, the tone is set for the novel’s remainder. The trigger for its particular investigation into death is Critchley’s discovery of a mysterious collection of papers belonging to his deceased friend, Michel, in which he finds an odd set of hand-drawn charts, resembling astrological maps. Michel’s own chart accurately predicts events in his own life occurring after its completion, including, troublingly, his death in a sanatorium in 2003, with Critchley concluding that, “Knowing his fate, he had simply lost the will to live.” Such composed reflection is rapidly dispelled upon discovery of a chart bearing Critchley's name, comprising intimate and private details of his and his family’s life, and, with alarming exactitude, the time, date, location, and cause of his death. Initially, this discovery inspires a quiet calm in Critchley . . .

Review by Jennifer Kurdyla

Catalonia, the home country of the revered mid-century writer Mercè Rodoreda, is a land of betweenness. Nestled in the crux of France and Spain, it is technically referred to as an “autonomous community” of the latter—in other words, depending on who you ask, perhaps its own country, perhaps not. As one of the most famous artists (alongside Salvador Dalí, who was also Catalan) to spring forth from this land of uncertain boundaries and identities, Rodoreda almost too perfectly represents this torn state of mind in her works of fiction, where characters and settings are constantly shifting between dreams and reality, apposite desires, nationalist claims, life and death. In her penultimate novel, originally written in 1980, War, So Much War, she demonstrates in phantasmagoric Technicolor brilliance the ways in which even such a cleft spirit can be a vessel for extreme beauty . . .

Review by Alex McElroy

Andrés Barba’s fiction is a zone of transformation, and in August, October and Rain Over Madrid, Barba’s first full-length works translated into English, the author attends to more understated manners of transformation: puberty, fatherhood, and grief. These transitions are not so much physical as emotional, and they signal a shift in Barba’s work, a move away from the gritty realms of prostitutes and orphans to the unspoken depravity of domestic life . . .

Review by Xenia Hanusiak

. . . It is only later, when you leave the room, that the weight of Mr. Gharani’s story drops and the orchestration of the recitative begins to unbalance your first perceptions. Mr. Gharani’s voice uneasily revealed that he was so badly abused he tried to commit suicide twice. An interrogator stubbed out a cigarette on his arm. He was kept in freezing conditions, sleep-deprived, and with alternating experiences of unpredictably blasted music and flashing strobe lights. The violin’s beautiful shudders, the potent guitar drones, and the flippancy of the American hoedown were the re-imaginings of this horrific incarceration. It was the soundscape of Mr. Gharani’s heart, of the existence he was forced to endure. In the clear hindsight of daylight, the experience is more sinister than I realized at the time. It was we who were being interrogated . . .

Review by Dustin Illingworth

At first glance, Ceridwen Dovey’s Only the Animals seems to slide easily into this literary tradition of creaturely appropriation. This collection of ten tales told by the souls of dead animals, finds Dovey writing in a semi-fabulist mode, though her thematic concerns—nothing less than what it means to be human—have expanded considerably from her debut effort. Each of the animals, having been caught up in a historical human conflict, tells the story of its own death. These vignettes are by turns heartbreaking and hilarious, and Dovey’s exceptional pacing ensures her readers remain engaged and enchanted throughout. No Disneyfied cautionary tales, however, are to be found herein. Dovey eschews sentimentality and easy moralizing, lending a sophistication to the proceedings that feels like a respect for the strangeness, and the ultimate unknowability, of wild consciousness. The eponymous animals are neither naïvely comic, nor possessed of the icy perfection and opacity of mythic beasts; rather, in their psychological richness and complexity of emotion they remind us nothing so much as ourselves—only sharper, wiser, somehow more than human. This is not to say that Dovey doesn’t find fertile territory within the abstraction of animality; indeed, she creates, and makes wonderful use of, an emotional distance through which human pain is refracted and made new. But there is never any bowing or scraping, no easy laughs or vulgar caricatures. Dovey’s artistry ensures that every revelation feels utterly earned . . .