Review by Stephen Sparks

It is partly to shore these beautiful fragments up against the sort of linguistic streamlining of toots into hills and shakes into cracks in drying wood that Paul Kingsnorth chose to write The Wake, his debut novel, set in England during the eleventh century Norman Conquest, in what he calls a “ghost language.” If this is his sentiment, he has imposed it on our twenty-first century vernacular to create a language which, against all odds, works. This language, an adapted version of Old English as it was spoken prior to the introduction of French words and influences that arrived on England’s shores along with William the Conqueror, has been made legible to modern readers by the removal of its most foreign elements . . .

Review by Lauren Goldenberg

Barbara Comyns's unique quality and authority of voice is already present in her second novel Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, now coming back into print from NYRB Classics sixty-five years after its first publication. Comyns’s skill is subtle and surprising as she tells the tale of Sophia, a young woman facing down one emotional (and physical) endurance test after another. On the copyright page Comyns has a note that I didn’t notice until after I had read the novel: “The only things that are true in the story are the wedding and Chapters 10, 11 and 12 and the poverty.” The frank bleakness of Comyns’s note almost made me laugh, even as it heightened the tragedy of Sophia’s story all the more . . .

Review by Rebecca Lentjes

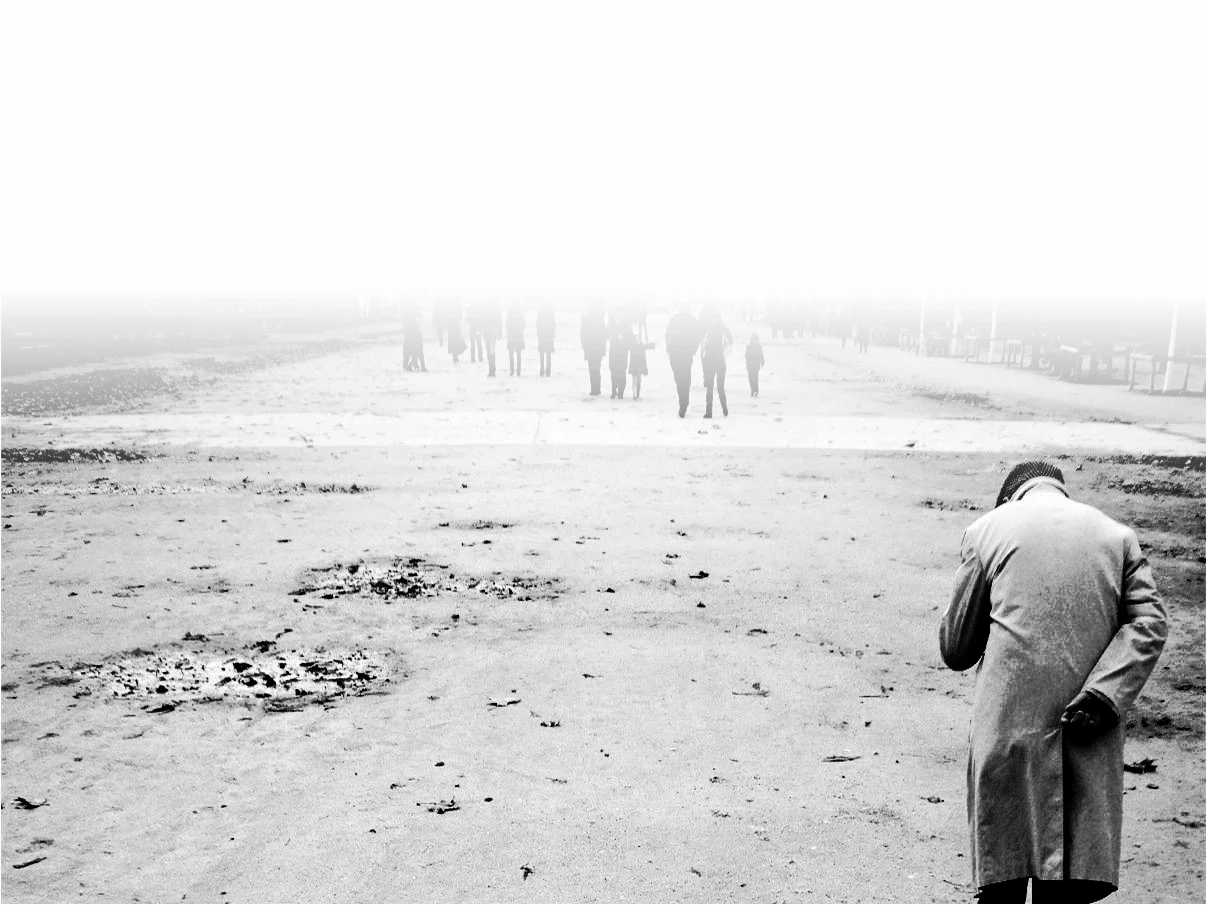

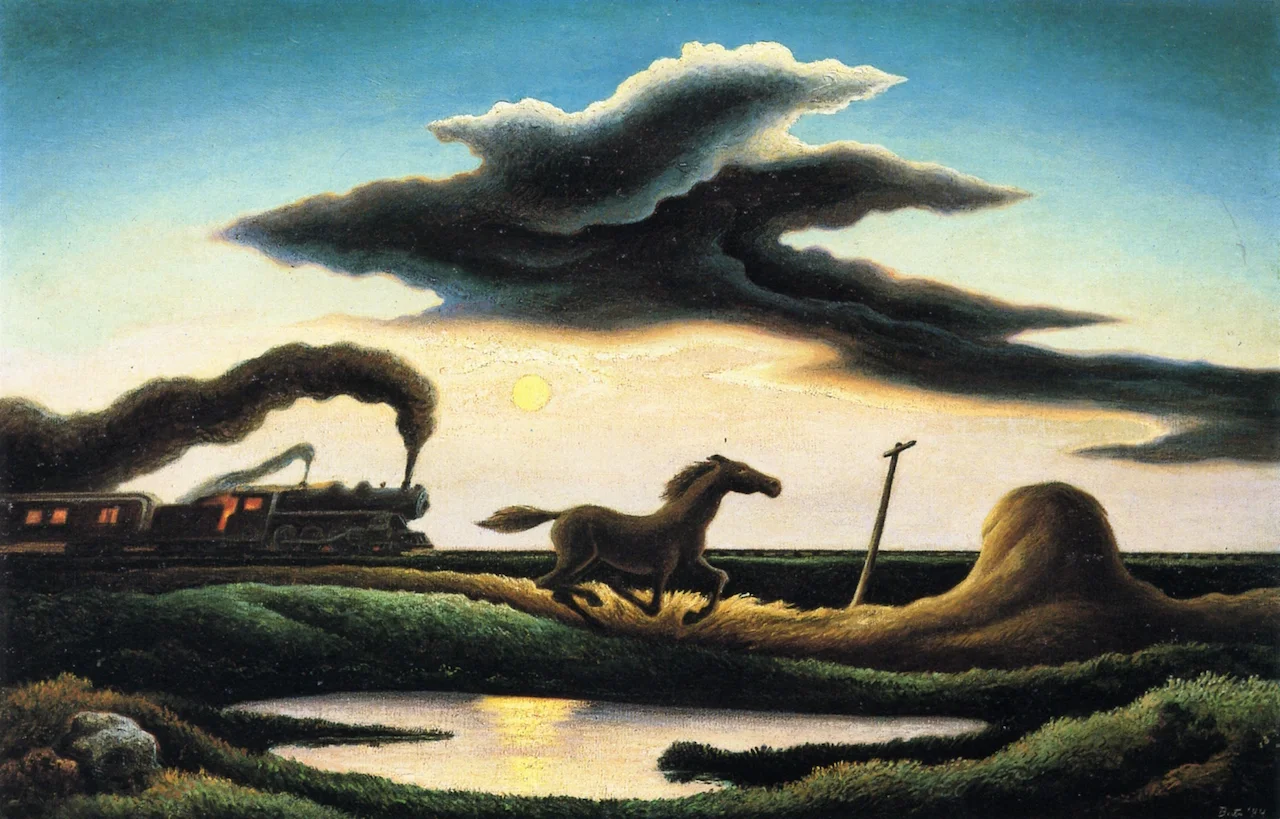

Despite his lifelong resentment towards the educational and musical establishment, Partch’s curiosity persisted throughout his whole career, and it was this curiosity that led him to seek out ignored sounds, found sounds, and new sounds. He heard music everywhere: in the forests of California, in the grunts and growls of illiterate hoboes, and in the tones between the notes of the ever-dreaded twelve-tone scale. Even more significantly, he heard this music as an element of storytelling rather than as an event in itself. Partch never allowed any one element of his music theater—not even the music—to dominate the whole. Instead, the usually “separate and distinct” elements of music theater coalesce to form another world, so that the parsing of these elements is made impossible. With Bitter Music, Partch conveyed his memories of the Great Depression via speech and graffiti, letting the music of the human voice transmit both the drama and realism of the human experience. Thirty years later, with Delusion of the Fury, he had transcended the limitations of words, and was able to convey tragedy, comedy, and divine justice in the knowledge that “reality is in no way real.”

Review by Henry Zhang

Grammar, for Diego Marani, is a set of divisions that result from interpreting one’s self and language. Meaning is differential: the raw material of people and language must be defined in opposition to each other, and in time, these differences sediment into things such as nationality and religion. And eventually, like a piece of chalk scrawling without a hand, this differential construction comes to be forgotten; the nation comes to see its identity as something positive and natural, stemming from providence. Yet each division, in the instant of its being drawn, gives hint of its own unnaturalness . . .

Review by Tyler Curtis

Subsumed by a strange growth, the protagonist of Guadalupe Nettel’s story “Fungus” concludes, “Parasites—I understand this now—we are unsatisfied beings by nature.” The sentence transitions ever so slightly, ever so gradually from “it” to “we” in referring to the fungal infection, but the effect is glaring in retrospect. She contracted the infection from an extramarital affair, and it’s spread all across both their bodies. As her unrequited obsession continues to grow, so does the fungus, in a manner both horrific and tinged by humor (“My fungus wants only one thing, to see you again”), eventually becoming indistinguishable from the fabric of her desire. Like “Fungus,” each story in Guadalupe Nettel’s Natural Histories pairs its characters with unknowable creatures whose trajectories parallel the inevitable disintegration of their domestic comfort. On top of the fungal fever dream: betta fish exhibit strange behavior and fight savagely as a woman’s postpartum depression grows apace with her husband’s increasing distance; an exotic snake appears while a father longs for his ancestral homeland; a cockroach infestation reaches a head as a family reaches a new apex of madness; a pregnant cat births a litter, subsequently disappearing as a doctoral candidate aborts her pregnancy . . .

Review by DeForrest Brown Jr.

Kalma and Lowe work very differently, operating with different rhythms, but each brought an equal amount to the table, and to further the idea that this performance was a sort of private dialogue between like minds, they didn’t seem to be playing for the audience. The pieces added up to something of a seance. The idea of “collapsed time” was particularly salient, as there were moments where the pieces felt incredibly short, despite being—in clock time terms—quite extended, generally upwards of ten minutes. Lowe and Kalma's separate philosophies of pattern and movement entangled, sparking new combinations of “cold,” calculating computer work and “warm,” biologic tones.

Review by Xan Holt

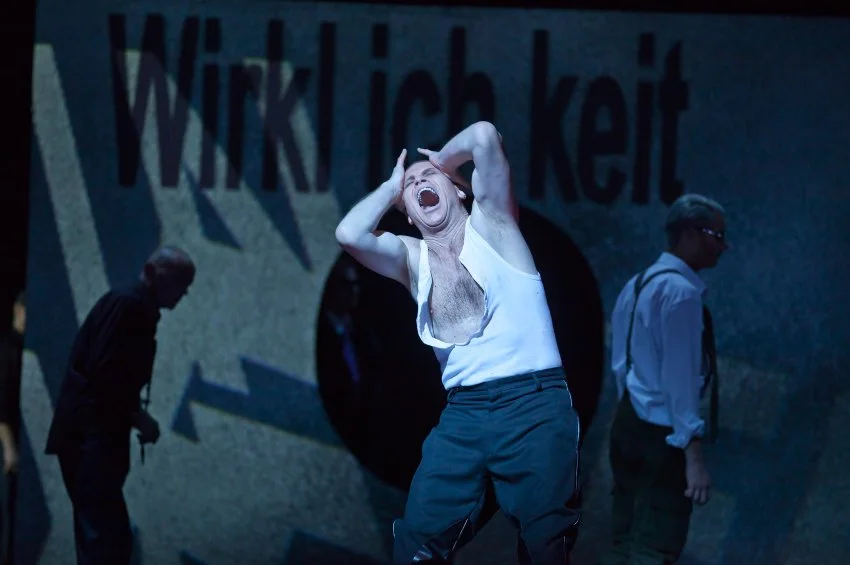

Elfriede Jelinek’s style bears unmistakable formal affinities with this “foreign” pastime of soccer. Her prose features nomadic chains of associations and circuitous sentences that carry the reader along for pages on end before abruptly sweeping him back to where he started. Productions of her performance texts often go on for hours without so much as a hint of a concrete development, to say nothing of a cohesive narrative or series of events. American theater, by contrast, largely shares in the nation’s appetite for palpable conflict, though Jelinek’s dramatic work does find some precedence in the language plays of Mac Wellman and Eric Overmeyer. Over the past forty-odd years of her artistic tenure, she has made a name for herself as one of the most linguistically challenging contemporary European writers . . .

Review by Alexandra Hamilton-Ayres

Although he is heralded as one of the great minimalist composers, Glass doesn’t endorse the term. When he was younger, putting on loft performances in 1960’s New York, he called himself, simply, a “musical theatre composer.” Today, he doesn’t describe himself as a film composer, either, but prefers to define his style as “music with repetitive structures.” In the autobiography, he discusses his visual artist friends from that period—the likes of Sol LeWitt and Richard Serra, who were the “official” minimalists. Because Glass associated with them, his music was correspondingly branded as such. He also writes about working with conductors who presumed his music was “minimalist” in a derogatory sense—in other words, that it was just a mere series of repetitions—and so didn’t bother to rehearse it properly, until they found out, all too late, that the score in question was far more intricate than all that, and was actually constantly evolving. It has always been the case that the superficial simplicity of a piece of music is only ever a mask of elegance, concealing a far more complex sonic journey. The assumption that Glass is therefore easy to play is a foolish one. This is also true of J.S. Bach’s music, where the melodies are simple and clear, yet the harmony is meticulously mathematical.

Review by Caite Dolan-Leach

Reading a detailed chronicle of the decomposition of a human corpse might sound like a grim undertaking. And in an obvious way, it is. But Viola Di Grado’s charming prose romps through chthonic worlds of nibbling insects, ammoniac seepage and shattering depression, using language that is both glib and scrumptious. She is a maximalist; her books don’t tiptoe subtly around obliquely concealed themes. She writes about death and depression without pulling any punches. This could sound like a tormented teenager’s self-obsessed ravings or a dull necrophiliac litany, but Di Grado has an almost supernatural ability to know when enough is enough, and she again and again delivers sharp, gorgeous demonstrations that she can do bizarre and lovely things with words . . .

Review by Mark Mazullo

Operatic composers are in the business of constructing selves, and opera singers are bound to be “something,” the kind of people for whom exists the phrase “larger than life.” This has been the case since the turn of the 17th century, when Shakespeare “invented the modern human being” (to borrow from Harold Bloom); and not incidentally, Shakespeare’s career ran contemporaneous with the birth of opera, invented in Italy as a style of “metaphysical song” (to borrow from Gary Tomlinson) that expressed the distance between interior and exterior, thus lending another face to modern subjectivity and its burden of giving names and forms to the nameless and unformed. Amidst all of this striving for “something,” how might a composer tell Lear musically in a way that allows equal time and space for nothing? How might Lear, in the face of Cordelia’s challenge, musically disappear? How might an operatic character occupy the ambiguous space of the unformed with music so unrelentingly forming it?

Review by Mona Gainer-Salim

Interpretation sometimes poses a grave risk to its object of scrutiny. By focusing so much on what art is about, is it possible that we are losing sight of what it is? Yoel Hoffmann’s newest work, Moods, has a peculiar, provocative relationship to the act of interpretation. Following Curriculum Vitae (2009), a dreamlike retelling of the author’s life, Moods continues Hoffmann’s loosely autobiographical project. Hoffmann weaves a rich web of memories, impressions and images, interspersed with frequent ruminations on his task as a storyteller. The text is filled with doubts and second-guessings—the first page alone contains no fewer than five pairs of qualifying parentheses. A playful challenge is aimed at the reader: abandon your assumptions about how a story should be told, abandon yourself to a narrative that moves in a different way, intentionally skirting the conventions of literary form . . .

Review by John Knight

Almost all of Emmanuel Bove’s work has been forgotten: twenty-eight novels under his own name, a few more under pseudonyms, many magazine pieces, a variety of short stories, and a meticulous if sporadic diary that reads almost like a manifesto of artistic solitude. This oblivion stings all the more for Bove’s having been immensely popular during his three-decade career—roughly between 1918 and 1945—when he wrote devastatingly concise and piquant odes to the consuming anxieties characteristic of the interwar years in France. About half of his work has been translated into English, much of it already out of print, but with this most recent publication from NYRB, Alyson Waters’s acute translation of Henri Duchemin and His Shadows, it suddenly seems as though we have a key into the novels, which might even provoke renewed, and certainly warranted, attention for this quiet and quietly forgotten writer . . .

Review by Jeffrey Zuckerman

Pulsing with nervous energy, swerving with alarming alacrity, driven to upend every assumption: Virginie Despentes’s Apocalypse Baby is a tightly wound spring of a novel. Its liberally sprinkled curse words and louche characters seem dredged from the dregs of our world—not so much invented as deployed to shock us into realizing how much we comfortable readers might take for granted. Sitting in a car, the Hyena tells Lucie, the narrator for much of the novel, with blunt casualness: “I like girls. I like girls too much. Of course I prefer dykes, but I like all girls.” There is an uncomfortable hint of deviancy in this line—but what else should we expect from a novel by Despentes?

Review by Ryu Spaeth

For Mia Couto in his essay collection Pensativities, the postcolonial project is not primarily political or economic; it is humanistic in nature, and literary in its means. Its aim is to reconcile history and myth, past and present, subjugator and subject. It brings together black and white, male and female, Africa and the West, young and old, the city and the bush. It seeks to mediate between the outside world and the life of the interior, and to translate between the multitudes within a person. It is the way of the poet, instilling the poet’s sensibility into issues of development and good governance . . .

Review by Christina Volpini

Dennehy has described his approach to handling found material as “musical vandalism.” In reference to this process, he has said, “Once I’ve hit on a few pieces of material that in my mind have ‘ineluctable modality,’ to steal a phrase from Joyce, then the true business of composition as vandalism begins. I become like a vandal joyriding through my material, oblivious to their separate poignant cries.” Though “vandalism” is often associated with negative acts such as destruction, defacement, and other activities with malicious intent, it serves as an ideal in Dennehy’s practice. This radical aspiration to vandalism is closely tied to his position as an Irish artist. Much Irish art, such as the literary works of Joyce and Beckett, has shown a penchant for fragmentation and the recontextualization of quoted resources. Vandalism has also served as a political act in the street art movement of Northern Ireland; marginalized groups have found a voice through the creation of political murals on community walls. Dennehy’s irreverent attitude towards his musical material is related to another of Irish culture’s distinguishing characteristics: Ireland’s simultaneous proximity and peripherality to the Western art world...

Review by Danny Byrne

In some perhaps not-so-distant future, when lab technicians in Google glasses are scanning back over the four- or five-hundred-year oddity that was the literature of Western modernity, the work of Enrique Vila-Matas may at least survive as a testament to its protracted death throes. Vila-Matas’s novels practice a peculiar form of high-literary bricolage, grubbing around in the rubble of the modernist tradition and finding there just enough material to cobble together a tragicomic monument to their own obsoletion . . .

Review by Adrian Nathan West

Questions hum in the background of Counternarratives, John Keene’s new collection of stories and novellas. Counternarratives extends an intuition already present in his first book, Annotations, that the themes the author strives to bring beneath his purview might best be approached obliquely. The tales in Keene’s newest work range from the chronicle of an insurgent slave in seventeenth-century Brazil to a dreamlike recollection of a passion-filled evening between Langston Hughes and the Mexican poet Xavier Villaurrutia. No two stories are formally alike: “Gloss On the History of Roman Catholics in the Early American Republic, 1790–1825; Or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows” combines philosophical lucubrations with straightforward history and excerpts from the journal of a slave, while “Acrobatique” opens and closes with a vertical line of prose, meant to symbolize the rope from which the famed black acrobat Miss La La hung suspended, a leather bit between her teeth. What unites them all is a meticulous attention to the weight and sound of words, a sensibility more poetic than prosaic, and a measured, deliberate meditation on the texture of black lives in history, taken not in the sense of grand narrative, but of what persists in the gaps, awaiting resurrection through art . . .

Review by Paul Kilbey

Who is listening, though? All these albums, really, are whispers. Not that they’re designed to exclude people—it’s just that to hear them, you have to lean in and pay attention. The quietness is structural. And a small audience is surely inevitable for music which, quite literally, doesn’t make much noise about itself. [...] And, indeed, we are all shouted at very loudly even when we aren’t listening to music: walking down the street, we are pitted against reams of exclamation-pointed imperatives—Buy this! Do that! The real challenge is to listen to as little of it all as possible. All of which makes deliberately quiet music a rare thing: something that doesn’t demand your attention, but nevertheless repays it if you give it. Who’s listening? People who’ve decided to concentrate on it.

Review by Julie Hersh

Mikhail Shishkin’s Calligraphy Lesson, a gathering of essays, short stories, and semiautobiographical digressions, is, as one of the narrators says in “The Blind Musician,” “fragrant with lilac and iodine.” It is made of the grotesque, the disgusting, the prosaically dead right next to the sublime, star-showers, frogs come back to life, love, and God. Shishkin takes these juxtapositions as his theme, and displays every kind of life as well as every kind of Russia; he lets us see underneath his own writing to the unmagical, unoriginal everyday . . .

Review by Andreas Isenschmid, translated by Michael Hulse

Krasznahorkai brings his enlightened, relativist present-day Westerners, alienated to a greater or lesser degree, face-to-face with the absolute demands that the sacred makes of existence. The medium through which the sacred speaks in his work is the sacred art of the past, approached in stories that, by the author’s account, often have an autobiographical basis. Readers who may themselves be indifferent to religion will not find themselves repelled by this book, with its breathtaking diagnosis of the times. For Krasznahorkai is no preacher: the dimension in which he works is one of questing, inquiring, doubting. Any overweening earnestness is undercut with the irony that accompanies his often eccentric seekers on their path. And he evades the greatest danger of all, inflated pathos, with the most surprising of his stratagems: while he writes of art purely as an expression of the sacred, he does so in the unemotional key of a scholarly expert discoursing on the technical aspects of art history. Hence the Russian icons are, on the one hand, windows through which there shines a world beyond this one, and through which we may gain visions of the hereafter, yet, on the other hand, the religious narrative is directly confronted with a strikingly well-informed art-historical essay on the traditions and techniques of icon painting . . .